By: Abbas Changezi

The Hazara people are one of Afghanistan’s largest ethnic groups, primarily residing in the Hazaristan region of central Afghanistan. Their history is one of survival, particularly following the ethnic Hazara Genocide (1892-1901) during the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan, which forced many to flee to neighboring countries like Iran and British India (now Pakistan). One city where Hazaras found refuge and gradually built a vibrant community was Quetta, in what is now Pakistan. Despite centuries of persecution, systematic discrimination, and even criminalization of their artistic expression, the Hazara people have maintained a resilient cultural heritage, including the revival and evolution of Hazaragi performing art.

For decades, the Hazara people, especially Hazara women, were subjected to brutal repression. Since the late 19th century, when Abdur Rahman Khan waged a genocidal campaign against the Hazara population, they were denied basic human rights and opportunities, their women profiled based on ethnicity, and subjected to horrific gender-based violence such as enslavement and rape. Against such odds, the Hazaras’ creative spirit managed to survive, but expressing it publicly became dangerous. Hazara artists who dared to perform faced dire consequences. Artists like the renowned female singer Abay Mirza (Dilaarm Aghai) were imprisoned, while others were silenced or forced to flee.

In the 1970s, however, a crucial turning point arrived. Radio Pakistan launched the first-ever Hazaragi Program, a landmark initiative that allowed the Hazara community to reclaim their cultural voice. For the first time, Hazara singers were given a platform to showcase their music in their native language. This program opened the door to a new era, encouraging Hazara artists to pursue their passion for singing and performing despite their challenges.

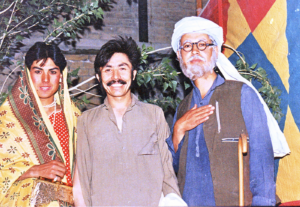

The 1980s brought further momentum with the emergence of Tanzeem Nasle Nau Hazara Mughal in Quetta, an organization that played a foundational role in developing Hazaragi theater and stage drama. Productions like “Maindar Khantoma,” “Alkhato,” and “Khaliq Shaheed” marked the dawn of a new chapter in Hazaragi performing art. Although humble in scale, these early performances were revolutionary in providing an outlet for Hazara’s voices. Singing, accompanied by the traditional Hazaragi musical instrument, the Dambora, became more visible, and artists such as Sarwar Sarkhosh and Safdar Tawakoli began to establish themselves as icons of Hazaragi music.

Notably, the first stage drama “Maindar Khantoma” featured Liaqat Ali Changezi, a male actor who played a female role—a reflection of the conservative social pressures of the time that restricted women from participating in public performances. However, the stage was set for change, and with time, women began to take their rightful place in Hazaragi art. The tele-drama “Shekasti Shab” featured female actors for the first time, breaking the deeply entrenched gender barriers.

The shadow of gender apartheid has always loomed over the Hazara people, and no regime has enforced this more stringently than the Taliban. Their rise to power saw the enforcement of strict gender discrimination, barring women from public life and placing heavy restrictions on artistic expression. However, despite these limitations, the Hazara community’s commitment to preserving its art and culture never faltered.

Today, thanks to social media and digital platforms, the reach of Hazaragi performing art is expanding beyond borders, becoming a source of pride and resistance. Hazara artists, including YouTubers, have embraced these platforms, creating content that resonates with both local and global audiences. The People Media channel on YouTube has gained popularity for producing short dramas that reflect Hazara society’s culture, struggles, and triumphs. Among their most acclaimed works is the series Maye Tabo, a deeply emotional portrayal of family life in the Hazara community. Another recent hit, Orphan Girl with No Destiny, showcases the powerful performance of young actress Nelofar Sultani, whose portrayal of hardship and resilience struck a chord with many.

These digital platforms have allowed Hazaragi performing art to thrive, even amidst repression. Artists like Kamila Nabizada, who often portrays maternal figures, and Hadi Sherzad, known for his emotional Hazaragi folk songs, have become influential figures in the cultural landscape. Through their performances, they entertain audiences and preserve a rich cultural heritage that continues to inspire future generations.

The story of Hazaragi performing art is one of perseverance and resilience in adversity. From the humble beginnings in Quetta’s small theater halls to the growing digital presence of Hazara artists today, the Hazara people have proven that no persecution can suppress art’s power. Their journey reflects the strength of a community that, despite countless struggles, continues to find ways to express their identity and humanity through the medium of performance.